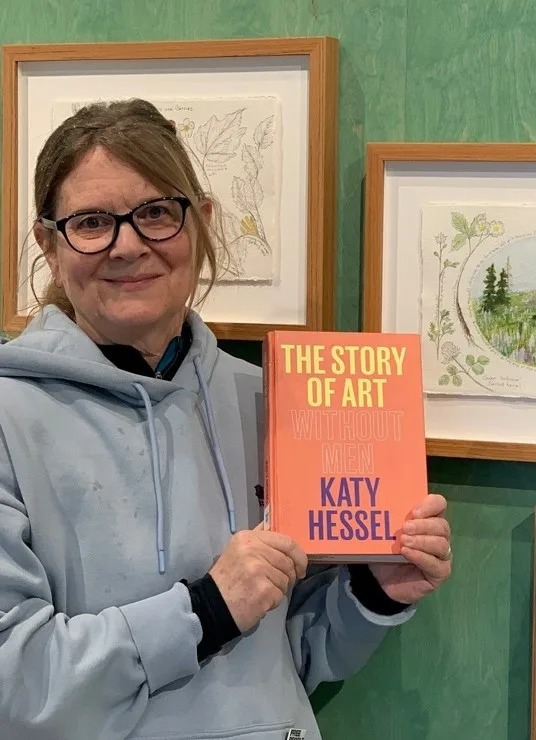

Director of the Center for Regional History, Mary Tyson, recommends The Story of Art without Men by Katy Hessel.

I first became aware of Katy Hessel’s work as an art historian through her podcast. The Great Women Artists Podcast sprung to life in 2019. it grew out of Hessel’s Instagram account with a similar name, “Great Women Artists.” Since 2015, Hessel has celebrated female artists daily, by sharing images of artwork from old masters to young graduate students. Her podcast is one of my favorites. Hessel has introduced me to so many artists that I didn’t know about and so many great art historians and critics who share her passion for making society aware of them. Her passion is contagious.

Hessel’s book, The Story of Art Without Men, came out in 2023, and I was so excited to see it at the Library! A rich resource covering a survey of art with a Western perspective, Hessel’s title comes from its predecessor, The Story of Art, by E. H. Gombrich, which, by its eighteenth edition, included only one female artist!

I think if you are a budding art historian, an artist, an emerging artist, an art lover, you would find this a great resource and you would discover, like I have, many artists that you will want to know more about.

The book is divided into five sections. Four of the five sections cover Modern, Post-Modern, and contemporary art. To state the obvious, there are many more women artists to help tell a story in the last 150 years than in the previous four centuries.

Hessel begins in the first section, “Paving the Way,” with the Italians in the early 1500s, specifically in Bologna. Bologna at the time was supportive of women in professions. Women were supported to go to the university there. One sculptor, Properzia De’ Rossi, had patrons, and created a marble relief, Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife, for the front of one of the largest churches at the time. Women in Bologna were encouraged to sign their work and to paint self-portraits to help make themselves known. Art historians have been able to study “a staggering sixty-eight women artists” working there between the 15th and 18th Centuries.

Some of my favorites that she included are painter, Agnes Martin, who lived a monk-like existence in remote New Mexico. She painted large mystical abstractions of the human condition, with titles like “Friendship” and “Happy Holiday.” Another is Nicole Eisenman, a painter of sympathetic figures, often grotesquely exaggerated to reflect our anxieties. Another favorite is Tracy Emin, a British artist, famous for shocking the public in the 90s by making the political personal and the personal public with an installation of her actual slept-in, unmade bed with empty vodka bottles and cigarette butts narrating her actual breakdown experience.

As Hessel writes, “Artists pinpoint moments of history in a uniquely expressive medium and allow us to make sense of a time. If we aren’t seeing art by a wide range of people, we aren’t really seeing society, history, or culture, as a whole…” More than any other art book in the Library, this one helps me to relax. I think it’s because of the feeling that someone has my artistic back and it’s Katy Hessel.